A different and better way to live

An exposition of the "builder's mindset" and its contraries

Here’s a pattern you might recognize:

You have some goals you care about. Say, for instance, you want to develop a personal exercise routine, or you want to make your tech startup profitable.

You know these goals will take a lot of discipline to achieve, and perhaps you’ve even tried and failed at them multiple times before. So you decide it’s time to “get serious” and really “lay down the law.” Perhaps you try to channel the spirit of Michael Jordan or some other hard-driving athlete you admire. So you sign up for a rigorous and competitive training program, and you come down hard on yourself anytime you start falling behind—first by chastising yourself to try harder, or compelling yourself to step up, and eventually calling yourself a “loser” and a “lazy-ass”, comparing yourself to the most dedicated athletes in the program, etc. Likewise, maybe you try to channel Steve Jobs’ famously demanding leadership style at work, both modeling and expecting long, grueling hours in pursuit of the ambitious growth targets you’ve set for your team.

At first, this approach might produce some amazing results. After a few weeks or months, you’re “head of the class” in your fitness program, and your company’s new subscriber counts are off-the-charts.

But after a few more months of this regime, the burnout starts to set in. Perhaps you start resenting your fitness trainer and the others in the program, and your self-contempt only grows as you inevitably miss more and more workouts or weigh-ins. Meanwhile a parallel process unfolds at your startup, where your team members start losing morale, complaining to HR, even threatening to quit.

After a few failed crack-downs that only seem to make everything worse, and perhaps after consulting with a fitness or executive coach, you decide to shift to a gentler, more compassionate, more process- rather than outcome-focused approach. Instead of berating yourself whenever you fail to live up to the “perfect” fitness routine, you listen to your body, celebrate incremental gains, and give yourself a break if you need to miss a workout here or there. Likewise, if your team members are underperforming, you try to cut them some slack, perhaps hiring wellness coaches or instituting “mental health days” to help prevent burnout, and praising them for their positive attitude and genuine efforts to implement your feedback, even if they never quite hit their monthly Objectives and Key Results (OKRs).

At first everyone feels happier and calmer with this approach. But as time goes by, you find that you’ve completely abandoned your exercise and fitness goals, and that your company has settled into a culture of comfortable mediocrity—with no one even seeming concerned by the growing chasm between your expected and actual revenue growth. So you feel like you need to “lay down the law” again—only this time at even greater cost, and against even greater resistance.

Ring a bell? I’ve observed variants of this oscillation between what I’ve called the “drill sergeant” and the “Zen master” approach in just about every domain of human endeavor: work, school, health, relationships, teaching, parenting, business management, communication, politics, you name it. We see variants of this conflict play out under the headings of “hustle culture” versus “self-care culture”; “missionary” versus “mercenary” leadership; “traditional” versus “progressive” education; “extrinsic” versus “intrinsic” motivation; “change-based” versus “acceptance-based” therapies; “outcome-based” versus “process-based” goals. And the solutions on offer all tend to boil down to variants of the same suggestion: “take the middle road.” Balance some acceptance with some change; set your standards high, but not too high; it’s “yes, and,” not “either-or.”

It’s not “yes, and,” but “neither-nor”

For context, “yes, and” originated as a technique for building on each other’s ideas in improv, and it works fantastically well in the many circumstances where two seemingly conflicting ideas or perspectives can in fact be reconciled with some creativity. But just as it’s a mistake to presume that two ideas can’t be reconciled, so it’s at least as big a mistake to presume that they can. Either way, we artificially constrain our hypothesis space when dealing with a given “A vs B” dichotomy.

Sure, it’s possible that A and B are actually just extremes of some quality that works best in moderation (a la Goldilocks’ complaints about the too-hot and too-cold porridge) or some continuum along which there are many acceptable “shades of gray.” But here are some other possibilities:

We have a misconceived or incomplete understanding of both A and B, such that they seem contradictory but are actually getting at different aspects or stages of the same legitimate phenomenon (like “empathy” vs “problem-solving”, which are both forms of “support” but are appropriate in different contexts).

One of them is actually right and one is wrong (as in the case of, say, “freedom vs slavery”).

A and B are both wrong (as in the case of, say, “passive” and “aggressive” communication, or “authoritarian” and “permissive” parenting), whereas some third option C is right (like “assertive” communication, or “authoritative” parenting). This is often the case when we have some underlying assumption (call it X) in our belief system such that A and B seem like our only alternatives, when really there are different and better alternatives, call them C+. The real solution may be to correct premise X to premise Y, which would lead to different downstream conclusions than either A or B. In other words: sometimes the solution to “black-and-white thinking” is not to “think in shades of gray,” but to think in color.

This last possibility is the one I believe best applies here: both the “drill sergeant” and the “Zen master” mindset share a common underlying worldview on which our lives do not fully belong to us, in that we have relatively little agency over the goals we set and the means by which we pursue them.

The “builder’s mindset,” by contrast, flows from a qualitatively different and deeply countercultural worldview: one on which all of our efforts can and ought to be organized around the ultimate goal of building and enjoying our own best life.

To show you what I mean, let me sketch a more vivid psychological picture of how you might experience your life when you’re operating on each of these different mindsets.

Life under “drill sergeant” rule

When you’re in “drill sergeant” mode, you tend to experience your life as some sort of test you’re supposed to pass, or a chore someone else has prescribed for you. Whether you’re exercising, or putting in long hours at your company, or spending time with family, or trying to go to sleep, the dominant motivation driving you to engage in these activities—and governing how you engage in them—is to prove your worth according to some conventional or communal standard. Maybe it takes the form of needing to “feel like you’re not a failure” or like you’re a “good person” or like you’ve “done enough” to lay off the bullying self-criticism for a while, though it’s never really “enough,” of course. Whatever the standard, it operates on you like a ball and chain, quite apart from—and often actively opposed to—what your wellbeing and happiness might require. “You can be happy when you’re dead,” your inner drill sergeant reminds you, perhaps softening this to “after you get the promotion” or “after you raise this next round” if you balk at the undiluted sentiment.

To the extent that you operate on this mindset, you give up some of the precious time and energy constituting your life to whatever authority—whatever “drill sergeant”—is getting to dictate your goals and standards to you. Not that you’d be in bad company, since nearly every culturally dominant moral tradition promotes some variant of the view that this is what you’re supposed to do. And even if you’ve explicitly rejected all such morally authoritarian views in substance, it’s all too easy to remain beholden to them in form—which turns out to be the more pernicious aspect of their influence anyway.

For instance, perhaps you’ve stopped caring about the religious or academic standards by which your parents or community leaders measured your worth when you were a child. So you try to carve out your own path as an irreverent, independent-thinking tech founder, all the while prioritizing your own health and fitness. But your fitness goals quickly turn into new arbitrary benchmarks by which your inner drill sergeant tyrannizes you. Or you find yourself constantly feeling anxious and guilty that you haven’t “gotten as far” or come up with anything as “disruptive” as the other irreverent, independent-thinking tech founders, like Steve Jobs or Jeff Bezos or whoever it is you’re comparing yourself to, had done by the time they were your age. And you obsessively focus on raising the kind of money or growing the size of team that would mean you’re “not a failure” in the eyes of the tech world, all to the detriment of thinking from first principles about what (if anything) you’re actually excited to build over the next several years of your life, and on what timeline you’d need to be raising money or growing your team (or not) in order to actually serve that specific aim. Or you try to emulate the “wartime CEO” ethos of Andy Grove or Ben Horowitz in a rigid, vaguely authoritarian way that you imagine they might approve of, while neglecting to consider the nuanced contexts in which this approach might be best suited (or not) to ensuring the long-term health and resilience of your company.

In other words, you’re trying to pass a different sort of test now—but you’re still fundamentally in “test-taking” mode rather than “building-a-life-you-love” mode.

Life under “Zen master” care

When you’re in “Zen master” mode, on the other hand, you tend to experience your life as a ride you’re being taken on, or a storm to be waited out and endured. Often in reaction to getting flogged a few too many times by the unrelenting blows of your inner “drill sergeants,” you focus your efforts instead on minimizing the stress of constantly trying to please them. Maybe you take a week or a month off work to go on a silent meditation retreat. Or maybe you just shift your focus to “keeping calm” and “hanging in there,” and not getting too attached to the success of any particular life project. I’m not talking here about refilling your emotional tank or calming your nerves so you can make better decisions that advance your life; I mean that you strive to be “more accepting” and “less judgmental” of how your decisions turn out and of how (or whether) your life is advancing, given how little control you ultimately believe yourself to have over these outcomes.

To the extent that this approach resonates, I submit that you may be trading in some of the excellence and ambitious goal-pursuit of which you may be capable for the peace and tranquility promised by some inner or outer “Zen master.” And if you’re trying to recover from the accumulated trauma and abuse you’ve endured at the hands of various “drill sergeants,” this path may seem like the only sensible recourse: better to ride out whatever failures, setbacks, and curveballs you encounter with equanimity, than to get bullied and badgered by your personal drill sergeants every time you fall short of their impossible standards of perfection.

These may sound, superficially, like opposite approaches, but notice what they both have in common:

Both the drill sergeant and the Zen master agree that pursuing high standards of excellence comes at the cost of your personal wellbeing. The drill sergeant’s solution is simply to sacrifice your wellbeing, while the Zen master’s solution is to sacrifice your standards of excellence.

More fundamentally, both mindsets take for granted the “standards of excellence” dictated by your local drill sergeant(s) as part of the furniture of the universe; the Zen master simply attempts to relieve some of the emotional burden of those standards by normalizing the fact that you can’t live up to them.

What neither mindset allows for is the possibility that we can define our own damn standards of excellence, grounded in our own independent judgment of the kind of life we want and the kind of work this will require. But, as I wrote in “The quest for psychological perfection”:

…I say we can do better. We can form our own ambitious conception of exemplary health and thriving, as suited to the particular fully-lived life we want to pour our whole selves into building and enjoying during our limited time on this earth—conventional standards be damned. And we can fight for that deeply personal vision of perfection with all our might, even when it means fighting our own psychological demons along the way. Not in service to God or country or our boss or our therapist or some stodgy inner drill sergeant, but in loving dedication to the builder within ourselves.

Life as a builder

To the extent that you are operating as a builder, you approach your life as the ultimate project you are in charge of shaping and overseeing (i.e., building), by your own efforts and according to your own chosen vision and values, with yourself as its ultimate owner and beneficiary.

So, if you wanted to assess the extent to which you’ve been on a “builder’s mindset” in the past week, you might ask yourself: how much of it have I spent choosing to do things based on how I thought they would serve and advance my life? Did I have clear, personally compelling reasons for the things I did, whether in the form of enjoyment and curiosity or because of the resources and further experiences they would unlock? When I felt bored, afraid, or resistant to a given task, could I clearly answer the question “why is this worth it”? And if I couldn’t, did I feel free to stop or change what I was doing?

A builder’s mindset could apply to almost any particular activity you might choose to do, and for an extremely wide range of particular reasons. Maybe you thought it would help you figure out what you like doing or whom you like being with, so you can then design more of your life around those things. Or maybe you saw it as a stepping stone toward a particular valued venture (like getting fit, or executing on a work project, or remodeling your house, or raising your kids). Or maybe you were doing it to gain the necessary knowledge, skills, health, money, or other resources for advancing your valued venture(s). Or maybe you were doing it to avert a disaster that could plausibly upend your life or the pursuit of your valued venture(s). Or maybe it simply brought you joy. The key question is whether you were motivated to do it on the basis of some such honest judgment (implicit or explicit) about how it would serve your life, while broadly accounting for any opportunity costs to your life as a whole. Maybe you were even mistaken in thinking it would serve your life in some way—in which case you took stock of the error, extracting new wisdom you can now bring to bear on future decisions.

This is what it looks like to function as a builder.

A difference of basic worldviews

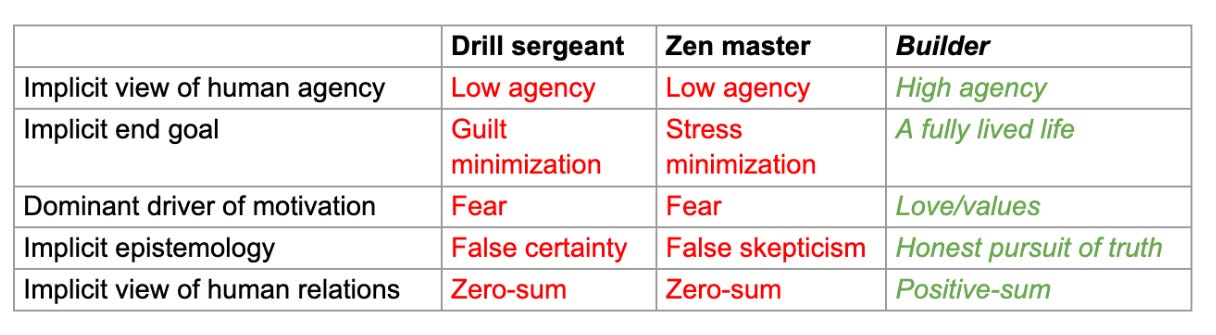

Here is a summary diagram of the implicit worldview I believe is common to the “Drill sergeant” and “Zen master” mindsets, and the contrasting position that the “Builder” takes on each issue:

As you can see, the “builder’s mindset” represents a fundamentally different set of underlying core assumptions about the kinds of beings we are, what we can do, and what is worth doing, compared to the other mindsets. This includes:

1. The belief that we can and should have agency, not just over how well we build, but over what we choose to build in the first place.

This is the view that we, as humans, both can and need to be the architects of our own lives.

This is the worldview expressed by Steve Jobs when he famously spoke of making “a dent in the universe.” Or, as he further elaborated:

“Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it… You can build your own things that other people want… And the minute that you understand that you can poke life, and actually something will, you know, if you push in, something will pop out the other side, that you can change it. You can mold it… Once you learn that, you'll never be the same again.”

By contrast, the “drill sergeant” mindset represents the whole variety of worldviews on which we are the servants of some moral authority outside of ourselves (be it God or society or “our country” or “the planet” or “those in need” or whatever “greater good” we have internalized)—an authority which we neither have the agency to question nor to ever fully satisfy. The “Zen master” concedes the lack of agency over how our lives actually go, but consoles us that at least we have agency over how we feel about this fact (insofar as we can choose to tolerate it with detached equanimity). In its most extreme forms, this mindset goes so far as to assure us that what happens to us really doesn’t matter because, at the end of the day, there is no “us”. As one scholar of Asian philosophy apts puts it:

“The Buddhist Enlightenment project is aimed at helping us overcome existential suffering, by dissolving the false assumption that there is an ‘I’ whose life can have meaning and significance.”

2. The view that exercising your agency to build your own fully-lived life is a self-sufficient end goal, needing no further justification or permission.

A builder views her life, lived on her own terms, as the ultimate value that organizes and gives meaning to all of her more particular goals and concerns. Viewed in this way, life is inherently a constructive project, involving the creation of new ideas, tools, relationships, and environments that sustain and delight us.

By contrast, the “drill sergeant’s” ultimate concern is with minimizing our failures in the eyes of whatever thankless moral authority or higher power presides over us; and the “Zen master’s” ultimate concern is with minimizing our stress and suffering through the literal “blowing out” of our passions and cares (i.e., “nirvana”). Both are concerned primarily with the avoidance of negatives, rather than the pursuit and creation of something positive.

3. A primary motivation by love and values, rather than fear.

If we set the conception and enactment of our own fully-lived life as our end goal, then we need never face a conflict between what we want to do—all things considered, given our best understanding of the causes and consequences involved—and what we “should” or “need to” do. We thus come to be motivated primarily by a positive conception of what we love and the positive life we want to build, rather than primarily by the (self-)judgments or discomforts we fear and want to avoid.

4. An epistemic commitment to living for real, not merely for pretend

On a builder’s worldview, our ultimate endgame is to actually build and enjoy our own best life here in reality—not to put on a mere show of doing so. This means having the intellectual ambitiousness to form our own sound, rational judgments about what’s true, what’s possible, and what’s worth doing in reality, and the self-honesty to safeguard those judgments against the lure of self-deception.

By contrast, both the drill sergeant and Zen master share an implicit pessimism about our ability to form our own sound, rational judgments about reality. The drill sergeant copes with this pessimism by conjuring up a higher authority to whose judgment we can defer (whether under the guise of “faith” or “divine intuition” or whatever we call it); whereas the Zen master counsels us to accept our ignorance and refrain from lending too much credence to any of our judgments (cf. the virtue of “intellectual humility”).

4. A positive-sum approach to human relationships

This understanding of human life as a constructive, positive-sum project of creation leads to a fundamentally positive view of other humans and of our relationships with them. By contrast, the drill sergeant and Zen master share an implicitly zero-sum worldview on which our only choice is, essentially, to “kill or be killed”—and again differ only in which side they happen to come down on.

Don’t throw out the builder with the drill sergeant

Apropos of the scenario with which I started this article, some of the world’s most inspiring builders—like Michael Jordan and Steve Jobs—commonly get mischaracterized as “drill sergeants.”

Part of what makes it so hard to differentiate these mindsets is that they do, in fact, sometimes bleed together; many ambitious builders (Jobs and Jordan being no exception) have had to combat their own inner drill sergeants at some point in their lives, and this has probably shown up in their leadership approaches. Plus it can just be really hard to distinguish these mindsets by observation of others, given that they can look and sound almost identical from the outside: what distinguishes the “builder” from the “drill sergeant” and “Zen master” are not any particular actions or utterances as such, but the underlying motivations that give rise to them.

Like the "drill sergeant,” for example, a builder may have cause to assume critical or demanding tones when the success or failure of a valued project is at stake. To take up our earlier example, it may be appropriate and even necessary for a startup executive to express profound disappointment with herself and/or her team members when they fall short of revenue targets that may make or break the company’s survival (and, with it, all of their jobs and the mission that brought them together in the first place). Such existential threats are endemic to any startup, but that’s all the more reason to care deeply about them and hustle to prevent or minimize them, if one wants to build the thing badly enough.

Unfortunately, our flinching fear of the drill sergeant has made us wary of exacting standards and accountability as such—even for outcomes we have every reason to deeply, personally care about as builders.

Both Jordan and Jobs blossomed into highly confident, highly intentional, and, yes, highly demanding leaders in the later parts of their careers. Both have been called “tyrants” and “bullies” by many for their dogged pursuit of excellence; and both were also credited with inspiring people to new heights of greatness at their valued endeavors. As one former Apple employee recalls:

“In the Macintosh Division, you had to prove yourself every day, or Jobs got rid of you. He demanded excellence and kept you at the top of your game. It wasn’t easy to work for him; it was sometimes unpleasant and always scary, but it drove many of us to do the finest work of our careers. I wouldn’t trade working for him for any job I’ve ever had—and I don’t know anyone in the Macintosh Division who would.”

What you had to “prove,” in other words, was not your ability to pass some arbitrary test of worth; it was your ability to add value to the shared project for which he had hired you. The experience of living up to that standard each day inspired countless Apple employees to do the best work of their lives—which they wouldn’t trade for anything.

Likewise, as Jordan explains in the 2021 Netflix documentary The Last Dance:

“I think there were a lot of situations where people were critical of the way that I proceeded, but I had a mission, I wanted them to understand what it took to win. Winning has a price... I wanted to make sure they were prepared for the worst, especially in competition. I'm pretty sure there were times they weren't happy with me. I think if you look back now, I'm pretty sure they are, based on what we achieved and our success and what we were able to overcome. As a leader, sometimes you're not gonna be well-liked, but you have to pull them along because you know it, you've experienced it, you understood that the other side of that road is success, so the gratification will be there once we're over that hill.”

That gratification did come, together with enduring gratitude for the players and human beings he helped them become. But Jordan did not presume that everyone wanted to live and play as he did, and he respected his teammates’ individual agency as deeply as his own. Toward the end of the same interview, Jordan remarks, with tears in his eyes:

"I don't have to do this. I'm only doing it because it is who I am. That's how I played the game. That was my mentality. If you don't want to play that way, don't play that way."

This is the mentality to emulate, if you want to emulate Michael Jordan. If, on the other hand, you try to emulate his "meanness" without his corresponding clarity of purpose and deep respect for his teammates, then don’t be surprised if this only leads to slavish passivity and burnout.

The upshot: check your “why”

If you’re worried you may have slipped into “drill sergeant” mode, whether because you’re getting burnt out on your projects or you’re being overly harsh and critical with yourself or your team, don’t just reflexively slip into “Zen master” mode, or vice versa; instead, see if you can access and foreground your inner builder. A helpful way to check and re-orient your mindset is to ask yourself: “why do I care about this?” And for whatever initial reason you give (like “because I want to slim down” or “because I want this company to succeed”), ask yourself: “why do I care about that?”—and over and over again, until you get to the very deepest reason(s) you can identify.

If, at that point, you’re left with some arbitrary standard you’re trying not to fall short of, then consider letting it go, as this may just be your inner drill sergeant talking. But if the answer is a real and credible one, with the enactment of your fully-lived life as the ultimate value at stake, then give it everything you got—including the rude awakenings, growing pains, and, yes, ruthless self-discipline that every worthwhile building project, and every fully-lived life, will sometimes require.

If you’re a venture-scale founder who resonates with the builder’s mindset and wants help bringing or keeping it on board, book a coaching session now. Everyone else: feel free to leave a comment below, or become a paid subscriber and claim your complimentary 1:1 Zoom chat, or subscribe for free and stay tuned for more content like this:

Hi, found this from a link on twitter. I appreciate the "thinking in color" idea, that drew me in—it's a good way out of black/white->grays->then what? sequence which comes up everywhere (e.g. politics.)

The way this is written threatens very much to establish "builder" as just another thing you "should" be, to be drilled-towards or zen-ed away from. I do not think "be a builder" is actually the right way to give this advice. And citing figures e.g. Steve Jobs as paragons of this virtue sets them up as people you "should" be like also—which is very likely to produce a narrowly-conceived idea of the person someone should be. Most, or much of the time, up to some point in their lives, Jobs/Jordan/etc probably *were* acting out of a sense of doing what they "should"/proving themselves, but one that was very coherently-held, so they were able to flourish as that version of themselves without actively employing the taxing drill-sergeant emotional posture.

The word "Builder"—and the figures you cite as inspiration—is better thought of as a sketch of what a flourishing/agentful person looks like, rather than what a specific good life looks like. It can be a revelation to learn that neither oppressive discipline nor painless detachment is necessary to live, and that a life with neither is desirable. The word "Creative" will resonate better for many people, in the sense that the fundamental choice to be made over and over is: out of all the general possibilities of my life, which one will I choose to create? Like creating art, or writing: you cannot be successful creating what you think you *should*. To step free from "should", and recognizing the *choice* in writing, art, OR life (which feels I think like a certain relationship to "fate", or the concept of "identity", the Buddhist direction is unavoidable)—this is what we are pointing to.

Your last advice, to ask yourself over and over"why do I care about that"—including "why do I want to be a builder?", "why does the word builder appeal to me?"—is in my opinion the critical *skill* it really takes to live in flourishing way. The drill-sergeant voice seems to come in when the answer to "why" is "to avoid facing the pain of not being seen/never being worth anything"; the zen voice appears as an answer "why should I have to prove I am worth anything"; the rabbit-hole of "why" can lead you to why you believe you need to be worth something and why you believe you are not.

Wow, this was so well written and I resonate deeply with it (in many ways). Thank you for sharing!