No such thing as intrinsic motivation

“I love every day. I mean, I tap dance in here and work with nothing but people I like. There is no job in the world that is more fun than running Berkshire, and I count myself lucky to be where I am." —Warren Buffett

We’ve all longed for and, if we’re very lucky, occasionally inhabited that sublime height of human experience where our work becomes a joy in itself: where we’re fully, happily engrossed in the problems we’re solving, where we love the people we’re solving them with, where there’s no sense of counting on some promised future payoff to justify having spent our time and energy on this work—because the work is truly its own reward.

Most psychologists would describe us as “intrinsically motivated” in this scenario, meaning our desire to engage in the work flows directly from the nature of the work itself. We’re motivated by, for instance, the excitement or curiosity it stimulates, or the immediate sense of competence it provides—rather than by any future reward or consequence we expect to receive from it. And they would contrast this with the times when we’ve been merely “extrinsically motivated”: for instance, when we were working primarily for the sake of a paycheck or promotion, or to avoid getting in trouble with our boss.

On this conceptualization of the different ways we can be motivated, which has dominated not only psychology but also related fields like education and management, intrinsic motivation emerges as the clear winner. Decades of research demonstrate what most of us probably know from observation and experience: that we learn better and perform better when we are actually interested in what we are doing, largely due to the greater sense of ownership and agency we experience over such activities—a sense of choosing them freely and for their own sake, rather than being pressured or coerced into them “carrot and stick”-style. And any observant teacher can accurately guess which students will show better understanding and retention: the ones who read about the Civil War to satisfy their own curiosity and thirst for knowledge—or the ones who do so to avoid getting grounded by their parents?

In light of such research and common-sense observations, there is a tendency to regard the use of external incentives as a necessary evil at best, and as actively undermining human autonomy at worst. This latter worry largely dates back to an influential early series of studies in which external incentives seemed to undermine people’s intrinsic motivation for the tasks being incentivized. These findings support in principle the worries of many progressive educators and management experts, who caution that grades or financial incentives may inadvertently kill the natural human inclinations toward self-directed learning and growth.

Less widely discussed is later research debunking these early findings, and decisively demonstrating that “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” motivators can work synergistically. But the problems go deeper than simply balancing out an overly extreme view with updated research. My view is that the entire “intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation” distinction is profoundly misconceived. The phenomenon illustrated by the Buffett quote above should not be described as intrinsic motivation. “Intrinsic motivation” does not exist. It’s an illusion that obscures the most salient feature of meaningful, enjoyable work: the felt understanding of its value relative to the whole complex network of causes and effects that constitutes the life you’re building.

Causes and effects versus “carrots and sticks”

One serious problem with the traditional “intrinsic/extrinsic” model is that it paints over two vastly different forms of “extrinsic” motivation with a single brush stroke.

Consider, for example, two different sets of “external” reasons that might motivate someone to engage in a difficult and largely unpleasant task, such as preparing for a medical board exam.

In the first case, the student is motivated by an understanding of how acquiring and demonstrating mastery of the material will serve her eventual goal of becoming an excellent doctor. For instance, she understands how fluently she’ll need to be able to call up the anatomical knowledge being assessed on the exam in order to operate on her future surgery patients safely and effectively; and she can envision various other aspects of the path from struggling through this material and earning this qualification to enjoying the career satisfaction, intellectual challenge, meaningful impact, and financial independence that being a doctor will eventually bring. She is motivated, in other words, by a complex causal understanding of her chosen career path, the positive health outcomes she can effect by being on that path, and the kinds of work required to forge ahead. This understanding was presumably gained through extensive data gathering and reasoned reflection over time.

In the second case, the student studies for her boards because her parents have threatened to revoke her trust fund if she does not graduate from medical school—a goal she is pursuing primarily at their behest and for the sake of their continued support and approval. Note that the causal relationship between studying medicine and receiving her trust fund money is purely incidental, as far as the student is concerned: her parents happened to make the trust fund money contingent on a medical degree, just as they might have chosen to make it contingent on a law degree, or getting married, or being nice to grandma. Perhaps they have a rationale in mind for desiring that their daughter graduate from medical school; but that rationale, whether sound or not, is not what drives their daughter’s studies. Thus, her own independent, reasoned judgment is not the primary driver of her actions; her parents’ dictates are.

Surely these two students’ motivations are as different as motivations can be. The first student’s motivation is grounded in an independently formed conception of her chosen life, and a hard-won understanding of the complex causal interdependencies involved in building that life. The second student’s motivation reflects no such conception or understanding. Surely we would attribute greater agency and autonomy to the first student; and we would sooner trust the first student to operate on our heart someday.

For that matter, we would probably trust that first student more than we would trust her classmate who studies only when and because she feels “intrinsically” interested in the material. And when it comes time for our hypothetical surgeons-in-training to perform open-heart surgery on us one day, we would sooner trust the one who is motivated by the future prospect of our full recovery, versus the one who is simply pursuing her “intrinsic” curiosity as she pokes around in us. In fact we’d probably even take comfort in knowing that the surgeon’s salary and promotion depend on the quality of her patient care.

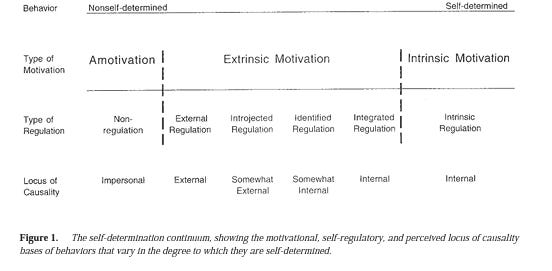

In recognition that not all external incentives are created equal, the originators of the “intrinsic motivation” concept in psychology have themselves moved beyond their own dichotomous “intrinsic/extrinsic” distinction, instead placing motivation along a continuum ranging from “externally controlled” to “integrated”:

On this model, the crucial characteristic to consider in assessing someone’s motivation is not whether it is intrinsic or extrinsic, per se, but the extent to which it is self-determined: that is, the extent to which we experience ourselves as freely choosing an action in service of our own needs, goals, and values, versus feeling as though it is in some sense imposed on us from without. Thus we can have more or less self-determined reasons for engaging in activities we do not find inherently enjoyable, and this difference makes all the difference in how we experience our extrinsic motivations. For instance, we freely choose to engage in all kinds of activities that are not inherently interesting or fun: we learn unintuitive new software tools because they will eventually help us in our work; we take our sick children to the doctor; we go through painful breakups in order to find lasting love. Far from undercutting our self-determination, such actions often call upon us to exercise courage and independent judgment in the face of emotional resistance, thus fortifying our powers of choice and agency.

But is human pleasure ever “intrinsic”?

Still, “intrinsic motivation” sits atop Deci and Ryan’s motivational continuum, implying that it remains the de facto gold standard: after all, the reasoning goes, there can be no more self-determined reason for choosing an action than for the direct enjoyment and satisfaction it provides. It’s one thing to endure the misery of a 60-minute treadmill run with the equanimity of someone freely choosing to live according to her values—but it’s another thing entirely to simply crave the pleasure of the run.

But this is where I want to pose a further question to Deci and Ryan’s model: what makes activities “intrinsically” pleasurable to us in the first place? Were they always? How many people do you know, for instance, who hold going to the gym (or running or yoga or some other form of exercise) as a deeply integrated part of their identity and values, and who don’t also enjoy it at least much of the time? Don’t distance runners famously enjoy even—or perhaps especially—the most “painful” parts of their runs? Does not that enjoyment flow, at least in part, from a visceral understanding of the greater fitness and endurance they are building for themselves over time through their efforts, and the felt, wordless knowledge of how these capacities will continue to enhance every aspect of their lives long into the future?

For that matter, would they still be able to enjoy distance running in the same way, or to the same degree, if they discovered—and really came to understand and believe—that it was hurting rather than helping their health and fitness over time? Would it literally feel as good to push themselves through that final mile, if they knew they were chipping away at their strength and mobility, rather than cultivating them, every time their foot hit the floor? I suspect not.

For perhaps the most dramatic and disturbing illustration of what’s wrong with the idea of “intrinsic pleasure,” consider the conditions under which those most allegedly intrinsic of pleasures—sexual arousal and orgasm—become anything but. When we derive ecstatic joy from such sensations, it is always in the context of what they literally or symbolically mean to us, not only in that moment but in the broader context of our lives: the celebration of enduring intimacy with a partner, or the affirmation of our own worth and power (a la “I’ve still got it”), or the embodied longing for a hypothetical future love (a la “This is what I want”). How, then, would we experience those same physiological sensations if they were inflicted on us against our will, by someone we fear will hurt, punish, or shame us soon afterward? As hard as it is to research such a sensitive and stigmatizing topic, the research that does exist on sexual arousal in non-consensual contexts suggests that such an experience would be agony, not pleasure.

As human beings navigating a complex external world by means of our rational-emotional faculties, we do not experience any activity in isolation from what it means to us as a being living in that world—including, inextricably, the causal consequences we expect to flow from it over time. Our conception of the future shapes our experience of the present.

Consider what you find interesting and enjoyable for its own sake, and think about when and why you find it so. For instance, I find my coaching and therapy work to be among the most consistently interesting and enjoyable parts of my job. As a lifelong student of human nature in all its complexity, I am naturally curious about my clients’ inner worlds and the connections between how they feel, think, and act. But my curiosity is not a fixed, irreducible constant: for instance, I’ve sometimes felt it flickering when I wasn’t as clear on the relevance of what a client was saying to the goals they purportedly wanted help with, or to the broader psychological phenomena I was constantly working to understand and integrate.

What makes these questions interesting to me in the first place, of course, is my expectation that the answers will ultimately benefit my clients. To the extent that I’ve found myself doubting the value of our current interaction to the client’s future growth and thriving, it makes sense that my enjoyment would flicker accordingly. In fact I distinctly did not enjoy the parts of therapy or coaching that I feared may amount to idle chit-chat—even if it was identical in content to the chit-chat I might tremendously enjoy in the context of a coffee date with friends.

Luckily, once I got better at catching and attending to such moments of flagging interest or enjoyment, they became objects of curiosity in themselves: how did we actually end up here? What’s the real reason we’re talking about this? Is there something I’m missing? Is there something my client is trying not to talk about?

After years of practice in reorienting myself to focus on such questions, I rarely even notice the “reorienting” step anymore. I simply experience my clients as endlessly, effortlessly fascinating. But this was not nearly so consistent or effortless when I was first getting started. From this perspective, my interest and enjoyment are not “intrinsic”—they are incrementally built and hard-won. Nor do they exist independently of my grasp of the future benefits I am working to effect for my clients, nor of the role of these benefits in supporting the rest of my life and concerns, financially and otherwise.

There are other aspects of therapy and coaching I do not “enjoy” in themselves, but that I find every bit as meaningful and ultimately rewarding as the “enjoyable” parts: the struggling through awkwardness, anger, and disconnection on the way to eventual trust; the searing pain of reckoning with horrific, senseless trauma and loss; the setbacks and disappointments when change does not happen as planned; the having to say goodbye when a client is ready to move on. These aspects fall squarely under the “integrated” motivation heading in Deci and Ryan’s continuum. Yet it seems grossly unjust to speak of my motivation for these aspects as a second-best substitute for some “intrinsic” ideal.

To pine for a world in which motivation is a perpetual flow state—or even to try to maximize the preponderance of this type of experience—is a mistake. The good-in-itself isn’t some special subset of euphorically motivated experiences within an otherwise dull and drudgerous life; it’s the whole set of richly motivated, mutually reinforcing actions that together add up to a life well-lived.

The height of human experience, demystified

Our capacity to envision our lives as an extended, integrated whole, rather than as a series of discrete, disconnected activities and events, and to bring that integrated conception to bear on every particular choice and decision, is the essence of our human agency. “Anyone who fights for the future, lives in it today”—and anyone who ignores the future, lives with the consequences of that ignorance today.

Rather than leaving our children, our employees, or our clients at the mercy of their “intrinsic” (i.e., unexplained) motivations to determine what goals they will or won’t achieve, we should teach them to generate their own motivations. That is, we should teach them to envision and select among the possible futures that lie within their reach, and to build an ever richer, more integrated understanding of the complex causal chains that connect their present to their future.

This, by the way, is the real reason to study history and literature: to learn about all the complex and diverse ways that human lives can go, and to extract from that vast knowledge base the practical wisdom to better architect our own lives. And is it not at least an implicit awareness of this fundamental interconnectedness of human knowledge and striving that drives a child’s “intrinsic” interest in learning? This is my lay understanding of the power of Montessori’s Five Great Lessons for captivating the imaginations of elementary schoolers, for example.

Simply exposing students to such ideas and stories does not automatically spark interest; rather it empowers them with an increasing database of knowledge and action affordances from which to do their own iterative work of determining what is worthy of their interest and why, and of directing their effort and energy accordingly. This work, I submit, is the one true path to self-determination, and to that ultimate height of human experience: the exercise of our fullest agency.

"Our conception of the future shapes our experience of the present. "

That's such a simple and yet profound and significant learning.

So much to love and comment on here. But the part about distance running was spot on to my experience. I have come to regard it as "chipping away at my strength and mobility, rather than cultivating them" in recent years, and with that, I only run when the weather and overbursting energy pulls me. And then, where I used to push through and take pride in never stopping, fighting to maintain at least a slow running pace when I felt I wanted to stop, I now just walk--not only without guilt, but knowing that it's actually BETTER than running. And I go out for runs way less frequently in general. Never winter running anymore!

What I understand and believe about running now keeps me from it most of the time (even though I generally am good at it and love it. But for love, I would never do it at all now.)