Worrying on schedule

What founders and people with generalized anxiety disorder have in common

Of all the frameworks and strategies I’ve shared with the founders I coach, there’s one tool they most often report finding helpful—even long after our coaching is complete.

I wish I could tell you it was “practicing a builder’s mindset” or “keeping a self-honesty log" or any of the various tools I particularly pride myself on developing. Mind you, founders have sometimes spontaneously touted the benefits of these other tools; just not as often as they’ve touted the benefits of this one.

The irony is that I was reluctant even to mention this tool to founders at first, because it’s so clearly not designed for them. Rather, it was conceived as a “stimulus control” treatment for the excess, hard-to-control worry that is the defining feature of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD). The basic strategy is to postpone your worry—i.e., your thoughts about all the various catastrophes that could hypothetically befall you—until a specific, pre-scheduled time and place each day. When worries do pop into your head at other times, you can just quickly jot them down or mentally file them away until your next “worry time,” and then shift your attention back to whatever you’re doing in the present.

While the notion of “postponing worry” has intuitive appeal (and decent research support) in the context of GAD, it’s not at all obvious whether or how it can help a founder. At times I’ve even worried (pun intended) that it might do them more harm than good. Founders often need to approach their worries with more urgency, not less. And their worries, like “what if we lose all of our customers to this software bug” or “what if we can’t make payroll next quarter”, are often both plausible and genuinely catastrophic for their companies.

And so when I did start presenting this strategy to founders, I issued a bunch of disclaimers like “only you know when it’s constructive to think about something and when it’s not,” “use this at your own discretion,” and so on. Then I gave them this ”postponing worry” worksheet and told them not to follow it too literally, but to take from it whatever nuggets of wisdom they find useful.

But what I’ve found is that there’s a fundamental similarity between the experience of early-stage founders and of those with GAD (even setting aside the non-trivial overlap between these groups): they are confronted with more hypothetical problems than they could possibly solve all at once, and yet they feel as if they should.

One of the most universal complaints among the founders I coach is that they can “never shut off”; they’re thinking about their startup when they go to bed (if they go to bed), when they’re at dinner with friends, when they’re playing with their kids, when they’re going for a run. And even during their self-endorsed working times, they find themselves anxiously micromanaging every software release when they should be focused on hiring a new product manager; or thinking about the bridges they’ll burn if they have to lay people off next quarter, when they should be focusing on their pitch deck for next week’s investor meeting.

I’m not talking about the times where they’ve misjudged the relative priority of the two problems; I’m talking about when they “know” they want to be focused on the second thing, but their minds “can’t help” coming back to the first thing.

The reason their minds “can’t help it” is because letting go of the worry feels akin to relieving themselves of responsibility for it. And there’s a kernel of truth in this feeling: as a founder, you are ultimately responsible for the fate of your company, which means it is on you to anticipate and prepare for the catastrophes that might plausibly befall it. And what’s more, it is dreadfully easy to default on that responsibility, if you’re not vigilant.

But what does “taking responsibility” actually look like? Clearly the practice of keeping every anticipated catastrophe in one’s mind at all times is both impossible and impractical, given that founders—like all human beings—can only think about so many things and be in so many places at once. This becomes all the more evident as the company grows and the number of moving parts involved in the company’s operation gets increasingly complex.

Besides, merely replaying an anticipated problem in your mind doesn’t ensure that you’ll make any progress toward solving it—especially if it’s distracting you from whatever actions you might be taking to actually solve it. What’s worse, it can give you the temporary illusion of working to solve the problem, when in fact you’re just emotionally protecting yourself from the eventuality where you fail to solve it.

To take responsibility for such a complex, multi-part endeavor as running a company, you need to take responsibility first and foremost for how you allocate the precious resource that is your own attention. In the wise words of Paul Graham, “distraction is fatal to startups.” So if your worries are distracting you from doing what needs to be done, then that’s the bigger worry to address.

The wider principle here is that you need to be purposeful and strategic in every decision you make about your company—including the decision of what you put time and energy into thinking about when. Like other strategic decisions, this requires an honest and holistic assessment of the chains of causality involved.

For instance, if you become aware of problematic bugs in the software your company is releasing, you need to be able to pull back and consider the fundamental factors contributing to this problem, and what it will take to address them. If it’s that you don’t have a competent product manager at the helm, then your time will be better spent finding and hiring a competent product manager than trying to catch every bug yourself while more irreplaceable aspects of your role get neglected. Once you’ve reached an informed judgment to that effect, then you have a context from which to quickly dismiss any further intrusive thoughts to the effect of “I need to go debug this code.”

Other times you might not have enough information to judge with certainty whether a given line of thought is worth pursuing—but you may know that right now is not the time to pursue it. If you’re doing something as complex as building a company, this is probably the rule rather than the exception of your mental life.

For instance, maybe you’re mid-interview with a promising job candidate (or mid-meal with a beloved family member you rarely get to see) when the thought pops into your head, “what if one of those bugs is actually putting our users’ privacy at risk?” You don’t know off-hand how plausible or urgent a possibility this is (whether because you actually don’t know, or because your judgment is being clouded by a momentary wave of anxiety). But you do know you don’t want it to distract you from what you’re doing right now.

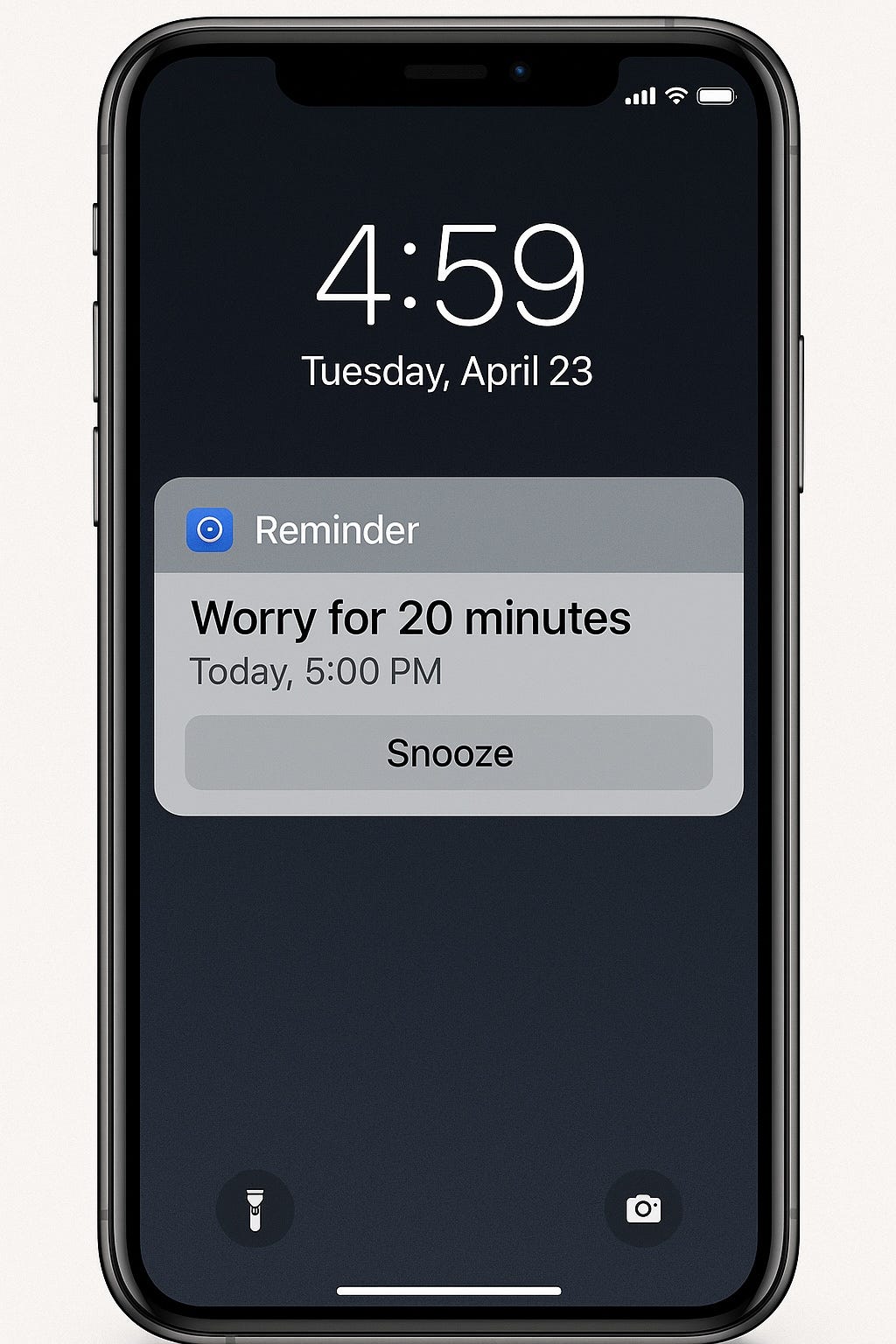

In such circumstances, a strategy of jotting down your worry in the briefest shorthand that will help you remember it later, like “privacy risk?”, and returning to it during your next scheduled “worry time” (or “standup” or whatever you want to call it) turns out to be invaluable.

In practice, this strategy amounts to delegating certain mental tasks and open questions to your future self. It ensures that you won’t let the issue drop entirely, while also giving you greater agency over when and how you attend to it.

Of course this exercise is just one of infinitely many possible forcing mechanisms for increasing your awareness and intentionality about where, when, and how you choose to invest your finite mental energy. Most founders don’t end up sticking too closely to the instructions in that worksheet anyway—and I still give those disclaimers to make sure they don’t. Rather they start finding their own ways to check in with themselves about the utility and timeliness of whatever they’re thinking about, and to set it aside for later if they judge it potentially useful but not timely.

From this perspective, the “postponing worry” tool isn’t really about postponing your worries. It’s about managing your own mind as purposefully as you manage the rest of your company, and realizing you can’t have one without the other.

The advice is not to be irresponsible for your concerns, but to fully and gleefully embrace total responsibility for choosing *not* to occupy yourself with an emotionally tempting concern. Not for the sake of emotional relief, but for the sake of the larger/real/ultimate/chosen "concern" or value that is otherwise being infringed upon by that nagging/anxious/emotional concern.

Hi Gena, thank you for sharing this technique - I have done part of it for many years and can confirm it works: writing down worrying (or even exciting) thoughts for “safe-keeping” helps a lot to focus on the task at hand.

However, how do you suggest processing all those notes afterwards in a coherent (and non-anxiety inducing) fashion? Also, isn’t it sometimes the best moment to work on sth when one is most excited/worried about it?