The story of Rachmaninoff's 2nd piano concerto—and why it's dedicated to his therapist

Dear readers: as you can see, I’ve really gotten into this Fantastic Builders series, to the point where it’s been hard to pull myself away to work on other things. I’ll go back to publishing other things eventually, but in the meantime I’d love to hear what you think about these stories, and—most important—what other inspiring builders you’d like to nominate!

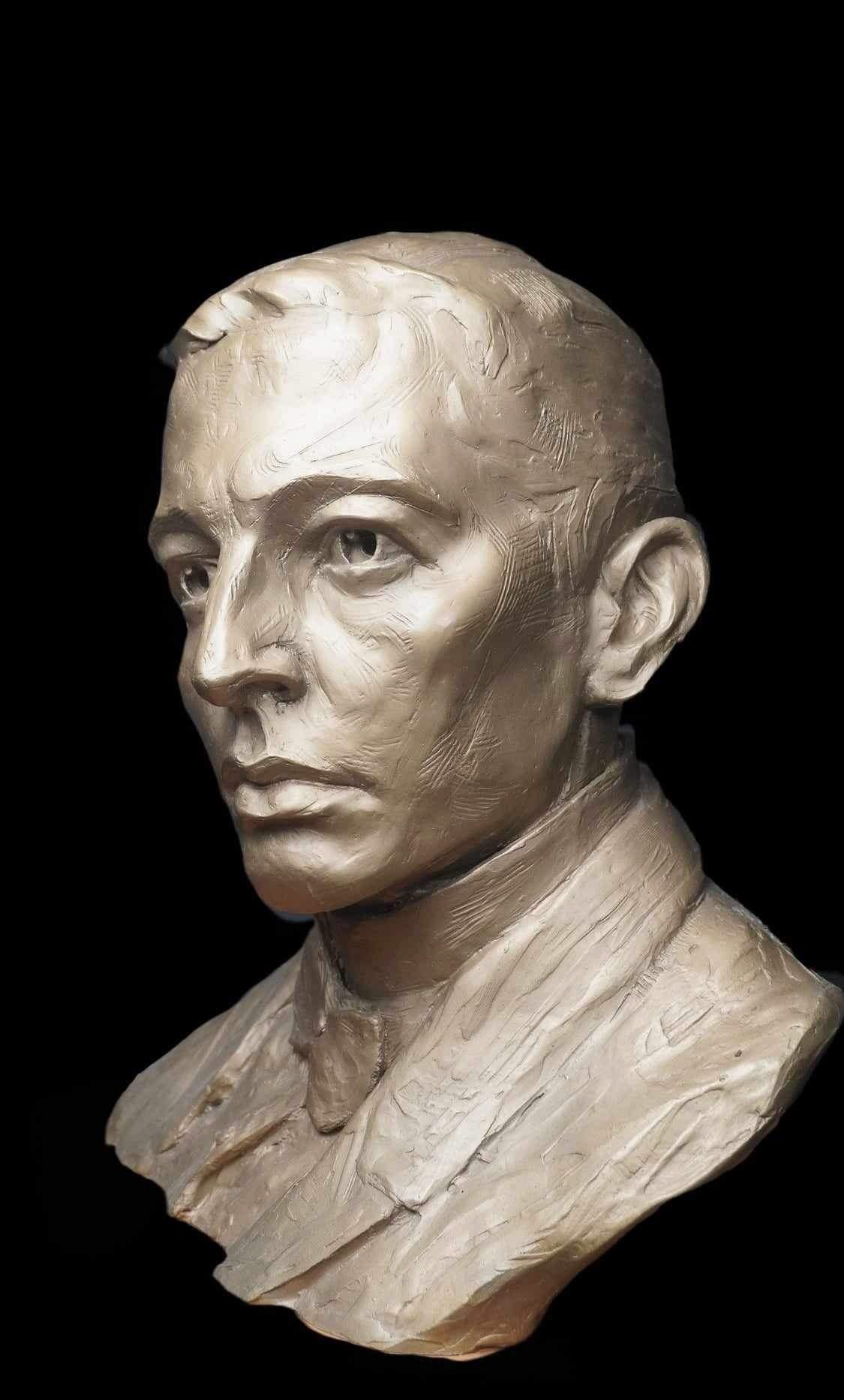

Builder spotlight #5: From “I ought to give up composing” to history’s greatest piano concerto in 3 short years (Sergei Rachmaninoff)

Principles on display: Your Flaws Matter Less Than You Think; Building Yourself by Building

The first time I fell in love, it wasn’t with a person, but with a piece of music.

I was 14 years old, and I was spending my summer on tour with the Blue Lake Youth Symphony Orchestra. The crown …